Comparing Ends of the World

(This is a translation of a review I originally published in 2022 in Finnish.)

Ends of the world caused by the undead and open-world video games are old staples at this point. Days Gone (Bend Studio, 2019) is both of these things, but still a very good game.

The game was originally a PlayStation exclusive, but in 2021 it was released for the PC as well . It was on sale on Steam in 2021, so I bought it, even though I had never heard of it before.

Days Gone is a bog-standard story about how suddenly zombies and everything shit. There is nothing surprising about the world or the characters in it: the undead, the in-fighting factions of the living, despair, constant preparation, ruthlessness, slavery, vigilantism, and sheer evil let loose by the cold, dead hand of the law.

MC Mongrels

The protagonist is Deacon St. John, “Deek” for short to his friends. His trusted sidekick is Boozer.

Deacon and Boozer are the last of their small-town motorcycle club, “MC Mongrels”. Down to earth and practical boys who have always been free to do as they pleased.

Deacon is mourning his wife Sarah, from whom he was tragically separated when the world ended and whom he presumes to have perished. A headstone has been erected for her, where the player can take Deacon to solemnly mutter his troubles.

The motorcycle club positions Deacon and Boozer as convenient outsiders. They are lone wolves who walk their own way, doing jobs for others in exchange for rewards. This opens up the game world to the player as a socially and morally relatively neutral space. The player has no pre-established allegiances towards anyone, so they are free to choose the alliances they wish to forge.

Apocalypse and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

The motorcycle constitutes the most original imagery of the game. Deacon and Boozer ride them, but then again so does everybody else. The game contains camps belonging to multiple factions, where the player may trade, spend nights, maintain their bike, and receive missions. All the traffic and logistics in the game seems to be arranged by motorcycles.

Enjoyers of post-apocalyptic fiction like to joke about how a bicycle would solve most of the problems that seem to bother people after the end of the world. Namely, cars typically cannot be driven, because all the roads have deteriorated and are full of derelict husks of vehicles. Cars can’t fit on the roads full of debris, but a bicycle would be easy to maintain, would not require any fuel, and would be small enough to weave through small spaces. You could also easily pedal fast enough to outrun at least the classic shambling kinds of undead.

The quiet bicycle would also not attract very much attention, and pannier bags can fit a lot of gear for the road.

A motorcycle is a curious half-way solution: smaller and more nimble than a car on one hand, but still loud and fuel-dependent on the other. The zombies of Days Gone do run fast enough for a bike to perhaps be a slightly unreliable means of escape, however.

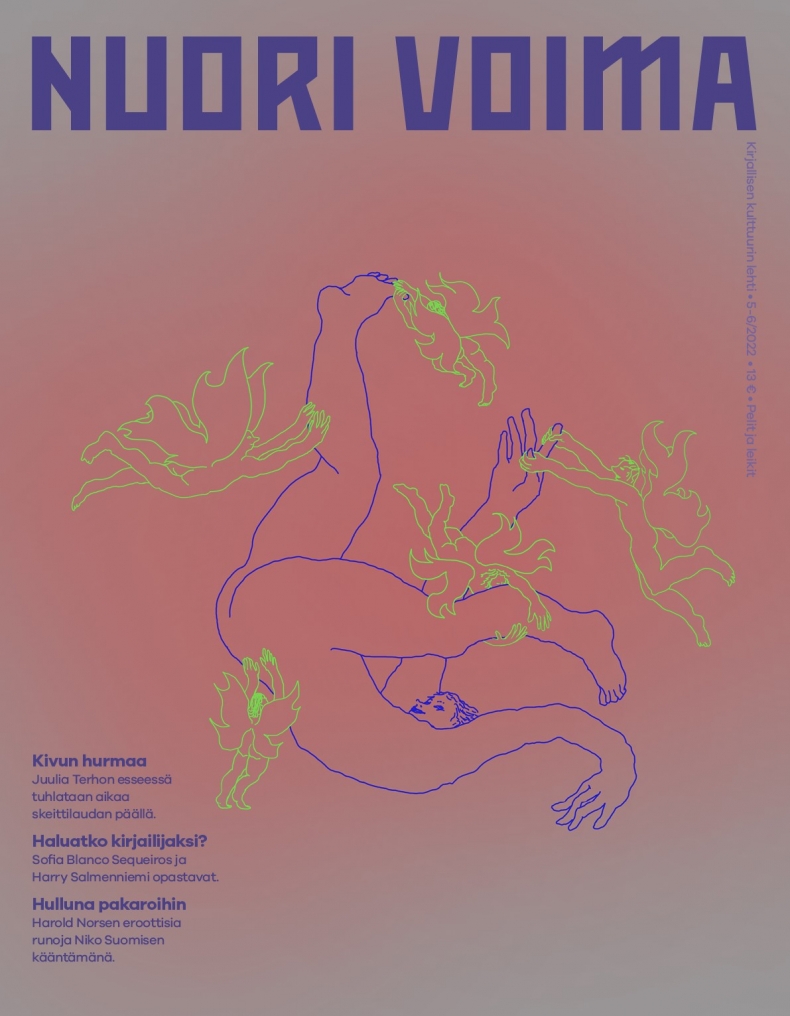

By the way, I wrote about the game series The Last of Us in the Nuori Voima magazine issue 5–6/2022 , from a perspective that admittedly doesn’t have much to do with this. Those games also feature creatures that can be considered “functionally undead”, as well as an end of the world or at least a collapse of organised society caused by those creatures. I mention The Last of Us here in passing because the means of transport in those games is a horse, which I found to be a more realistic pick than a motorcycle. A horse can also go fast when needed, doesn’t make a loud noise at least continuously, and most of all it does not require fossil fuels to run.

Technically impressive spectacle

Graphically, Days Gone is a very convincing work. The characters, animals and enemies have no cause for complaint, but I was particularly mesmerised by the landscapes. Bend Studio is a games company from a town called Bend, Oregon, with about 100,000 inhabitants.

The depiction of nature, light, and weather exudes a deep appreciation of the local region. The developers have also recreated many real Oregonian locations in the game and glazed them in a believable frosting of destruction and dilapidation. You can find side-by-side comparisons online.

In online discussions, the game has been well-liked and many people consider it underrated. As far as I can tell, it is a typical case of a game deemed bland by critics but loved by players.

I can understand why. The game works very well in a technical sense: shooting the zombies feels satisfyingly powerful and gory, and shredding muddy forest paths on the motorbike feels exhilarating. On the other hand, from a story-telling perspective, the game takes itself a little bit too seriously, the story is remarkably predictable, and the central characters disappointingly archetypical. Deacon has some emotional depth and multidimensional qualities, but all the other characters can be summed up in a sentence.

That said, the game doesn’t beat around the bush or try to hide its focus on the game-play mechanics. It is overtly proud of how smoothly it can render even hundreds of zombies on screen at the same time, and it features many game modes separate from the main campaign which focus solely on the gore fest.

Still more on that motorbike

In spite of all that, I was most intrigued by the motorcycle. It’s a very interesting symbol.

The motorcycle is very tightly coupled to masculinity. First of all it is the homosocial object that binds Deacon and Boozer; a channel for their friendship.

It represents freedom and individuality as well. Risk and defiance. Indifference and self-sufficiency. The outsider and the outlaw.

At the beginning of the game, the presence of the motorcycle felt very fresh and exciting. Here are we, two men, grim survivors in our denim and our vests. You and me, companions, inseparable. The motorbike felt like Deacon and Boozer’s own thing, a special resource and the key to their survival.

The game introduced the two main characters so boldly and powerfully—two unlikely anti-heroes still alive on the road—that the sexy, nonchalant allure of the motorbike was devastatingly undermined, when it was revealed that everybody else in the game rides them, too. It wasn’t just the intimate cornerstone Deacon and Boozer’s bromance, but merely the ordinary new normal in this post-apocalyptic Oregon.

My discomfort was sustained by the constant awareness of the fact that, even though this was a world full of motorcycles, there are no helmets to be seen. Even in the pre-apocalyptic flashbacks featuring Deacon and Sarah, where Deacon drives and Sarah holds on tight by his waist, they are not wearing helmets.

Zombie stories are always about society

Stories about the end of the world always pose the question: if you remove organised society, what are the things that don’t exist anymore, and what will replace them?

Here we could perhaps return to The Last of Us for a bit and think about symbols. Especially in Part II, right at the beginning, the game drops some not-so-subtle references to the American past. The means of transport is the horse, the game starts in the hearteningly sympathetic small town of Jackson, people look after each other in the face of hardship like it’s Little House on the Prairie, and at night they gather in the saloon to dance to the fiddle. Emotions are expressed and women wooed by means of the acoustic guitar.

There is a warmly fantastical side to the apocalypse: if only there were a smaller community easier to conceptualise, fewer responsibilities, more time and space to concentrate on rustic fundamentals. Drama and conflict arise from the unpleasant side of humanity: laws, equality and fairness get replaced with homophobia, cruelty, hatred, vengeance, rule of power, agony and injustice.

The world of Days Gone doesn’t feel so poetically balanced, but somehow broken. To me, Deacon and Boozer’s arc is an important merit to the story. They gradually learn to trust others again and ask for help, when setbacks prevent them from forever going it alone. However, it’s only a fleeting, inconsequential moment, and I wish the game had taken a step back and fully explored that theme.

The atmosphere of Zombie Oregon is paranoid and untethered. Deacon isn’t at home anywhere, but rather just angrily roaming around Oregon. Everywhere is full of distrust, grudges, want, naked persistence, and apathy.

Whereas the horse and guitar of TLOU compare the zombie apocalypse to the Wild West, the motorbike and the prominently featuring psychopathic death cult of Days Gone take the mood in a much more dieselpunk direction. Less Laura Ingalls, more Furiosa.

When I was writing this, I was supposed to add a link to a blog post I read, but I could never find it again. It talked about how at least American post-apocalyptic stories are often mind-numbingly similar: heteronormative, middle-class, and strangely libertarian. The central characters are white heterosexuals whose chief motivation is protecting the nuclear family. The fantasy about the disappearance of society has to do with how there is finally nobody to tax you and boss you around, but rather, you are now free to shoot as many guns as you like, build fortifications, only care about you and yours, and not give a fuck about anybody else. To boot, zombies even provide a maximally dehumanised target for the maximal violence enabled by the cessation of society.

The blog called for different, queer and norm-resistant apocalypses. I think the text even named some web comics that had played with queer ideas of e.g. what the end of the world might mean for the patriarchy, marriage, sexual morals, the nuclear family, or monogamy.

(If you recognise or are able to find the blog post based on that description, please let me know and I will add the link.)

In this light, the most interesting scene in The Last of Us: Part II might actually be the one with lesbian sex, weed, and armpit hair. In Days Gone, by contrast, Deacon makes a point to appropriately grieve his lost love and honourably reject the advances of a new woman.